Unmaking Americans

Reading Between the Lines of Trump's Denaturalization Policy

In the front of every new U.S. passport, nested between the photo page and the stamps, is a page entitled “IMPORTANT INFORMATION” in all caps. Along with warnings about drugs and not violating foreign laws, the page outlines the various ways American citizens can lose their citizenship.

But for the roughly 25 million naturalized U.S. citizens, the passport’s list is incomplete. The list of potential threats to their citizenship is expanded by 8 U.S. Code § 1451: the denaturalization statute.

For the overwhelming majority of naturalized citizens, denaturalization has never been a realistic risk. While many early 20th century denaturalizations took place to silence political dissidents, most of the 21st century denaturalization cases have targeted war criminals and terrorists that concealed their backgrounds on their visa and citizenship applications.

The statute has been used sparingly. Between 1990 and 2017, there was an average of 11 successful denaturalizations per year. During Trump’s first administration, there were 42 denaturalizations filed annually. But internal U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) guidance obtained by the New York Times indicates that the administration is trying to rapidly increase the number of denaturalizations. The guidance orders USCIS to supply the Department of Justice’s Office of Immigration Litigation with referrals for “100-200 denaturalization cases per month.”

By setting up another unrealistic immigration enforcement quota, the administration is pushing civil servants to make a choice: conduct lawfare against U.S. citizens or fail to meet your targets.

The Targets

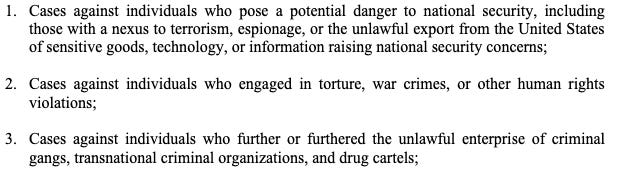

The quota does little to indicate whom the administration is seeking to denaturalize. That information came from a different memorandum, issued by Assistant Attorney General Brett A. Shumate during his first month on the job. In the memo, Shumate lists the administration’s priorities for pursuing denaturalization cases:

On their face, many of the priorities are reasonable. After all, numbers 2, 4, and 8 are explicitly what the denaturalization statute was created to address. But priorities 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9 are written intentionally broadly, such that they are likely to bring many referrals that are not actually legal grounds for denaturalization.

The Legal Limits on Denaturalization

The government cannot simply wish away one’s citizenship. The Department of Justice must first win in court. And such victories are rare; the denaturalization statute is written narrowly and courts have always interpreted it as such.

The primary1 two routes to denaturalization are civil proceedings and criminal revocation, both of which are limited to the review of one’s eligibility for citizenship at the time of naturalization. Unlike green card holders, naturalized citizens cannot lose their status based on crimes committed after naturalization.

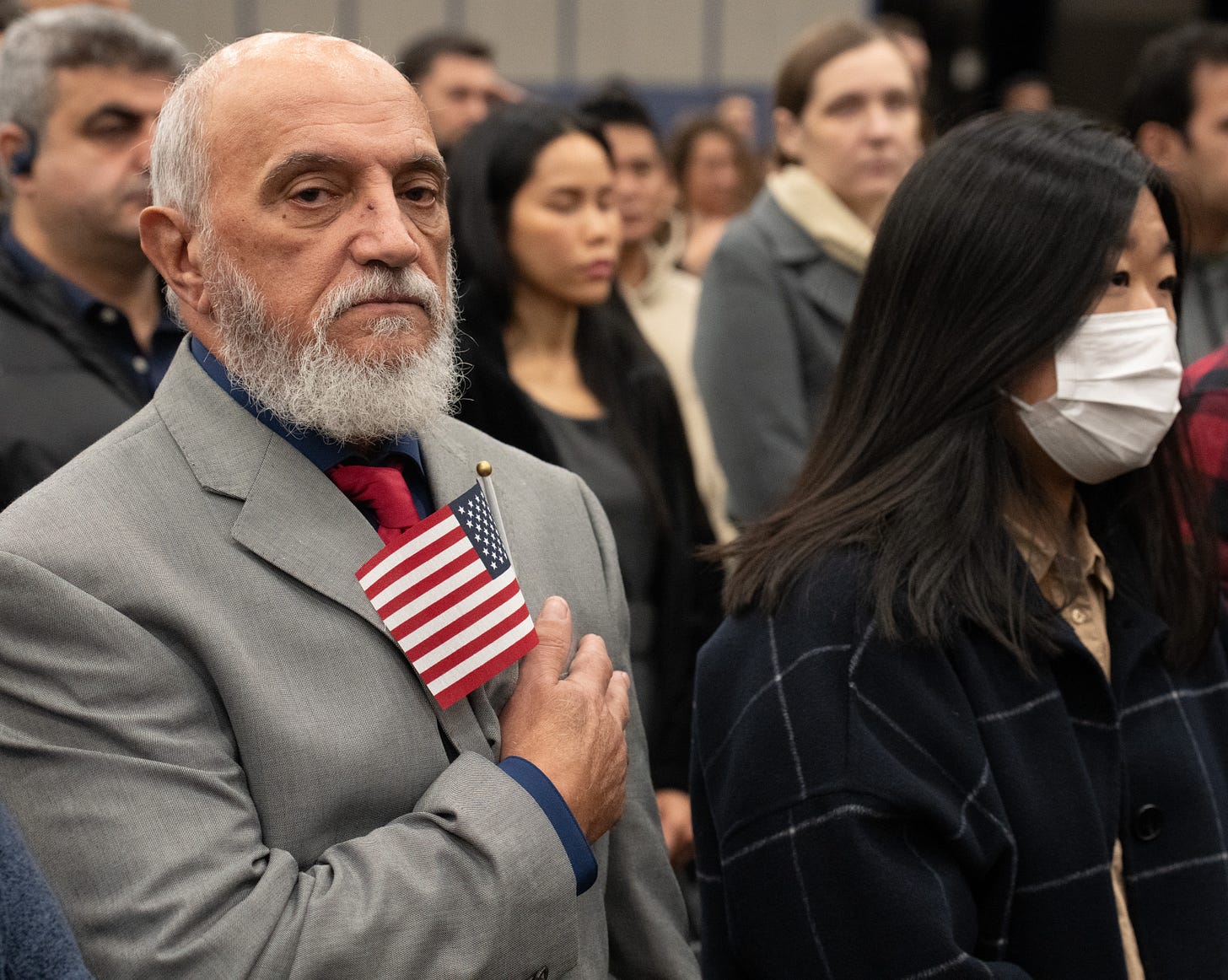

Denaturalization also requires a very high evidentiary standard. To denaturalize a citizen, the government must prove with “clear, unequivocal, and convincing” evidence that the citizen was ineligible to naturalize. That standard was hardened in 1943 in Schneiderman v. United States, which held that in denaturalization proceedings “the facts and the law should be construed as far as is reasonably possible in favor of the citizen.” If someone met the statutory requirements to naturalize and did not conceal any material information that would have prevented their naturalization, their citizenship cannot be revoked.

Digging into these requirements, two sit seemingly with considerable ambiguity: Good moral character and Attachment to the principles of the U.S. Constitution. But each of these has been litigated repeatedly to have specific meanings. Good moral character generally refers to a lack of disqualifying criminal convictions prior to naturalization, and attachment to the constitution is another McCarthy-era statute that bars members of the communist party from naturalizing.

The administration must be aware that many of the priorities listed in Shumate’s memo, particularly those referencing post-naturalization crimes, would not constitute a winnable denaturalization case.

Past Policy: Operations Janus and Second Look

The U.S. has failed at this before.

Operation Janus was the first operation in recent history to denaturalize on a large scale. It started early in the Obama administration, after it was found that due to a records management failure, some people who had evaded deportation had later successfully naturalized.

The first successful denaturalization under Operation Janus didn’t take place until 2018, nearly a decade after the program started. USCIS then stated that it intended to refer an additional 1600 denaturalization leads (revised down to 887 by 2019) to pursue. That year, DHS also launched Operation Second Look, an endeavor to review another 700,000 alien case files.

To take on this additional workload, DHS budgeted $207.6 million to hire an additional 300 special agents and 212 support personnel to detect immigration benefit fraud, investigations for visa adjudications, and visa overstay enforcement.

The administration has never released comprehensive data about the Janus or Second Look leads,2 but based on the fact that there have consistently been fewer than 50 successful denaturalizations in the years since, it’s clear that neither program uncovered systemic fraud.

Process as Punishment

If the administration understands that they cannot denaturalize people on many of the grounds distributed in the Shumate memo, why try?

In a recent interview on WBUR’s On Point, UCLA professor Ahilan Arulanantham posed this theory:

Of course you can have a huge amount of harassment and abuse of people if you bring criminal charges or civil denaturalization charges against them, even if they don't have a lot of merit and don't ultimately result in someone losing their citizenship. The government can do a tremendous amount of damage to people by bringing cases that are extremely weak.

Even if they fail, ramping up denaturalization cases accomplishes several of the administration’s goals.

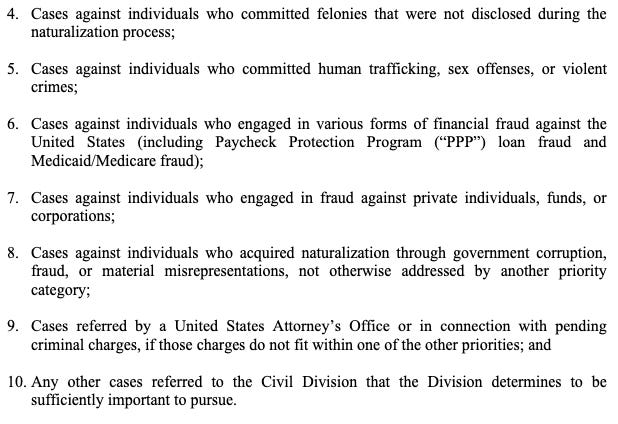

Widely publicized denaturalizations will likely cause many eligible green card holders to delay or cancel their plans to naturalize. This prevents immigrants from enjoying the fruits of citizenship, including voting rights, protection from deportation, and a wider range of sponsorship opportunities to extend residency rights to family members, decreasing total family-based migration. Those who dare to seek citizenship put themselves at risk of finding themselves in a courtroom, across from a federal prosecutor, seeking to uproot them from their home.

More broadly, weakening naturalized citizenship pushes the country toward the Trump administration’s theory of civic belonging. It advances a vision of civic belonging that is rooted in blood rather than choice. In a system where naturalized citizens can be stripped of their citizenship, they can never truly be equal to birthright citizens. An immigrant is forever an outsider, there is no such thing as truly becoming American.

The statute also describes two less-relevant grounds for denaturalization. Less than honorable discharge from the military, for immigrants who gained citizenship through wartime military service, and the §340(a) Proviso, a remnant of the Red Scare designed to denaturalize communists, socialists, and anarchists.

I have filed a FOIA request with ICE for more precise cost and outcome figures for both Operation Janus and Operation Second Look. I have not received a response.