No Witnesses

Behind New ICE Detention Walls

State violence is unfortunately nothing new to Minnesotans; Renee Good was killed within one mile of where George Floyd was murdered in 2020. Maybe that’s why Minnesotans have been diligent about documenting DHS violence. The shootings of both Renee Good and Alexander Pretti were recorded from multiple angles, leaving no doubt about what actually occurred. By threatening and attacking witnesses, DHS tried to make their actions in broad daylight invisible, but they failed.

The visibility of Good and Pretti’s murders cracked open the possibility for change and accountability. But what happens when violence is deliberately designed not to be seen?

Camp East Montana:

Fifteen minutes outside of El Paso, Acquisition Logistics, a Virginia-based defense contractor, is putting up tents. From Route 62, the low, white tents melt into the background of the Chihuahuan Desert, as if they were designed to blend into the landscape. The tents are part of Camp East Montana, a new $1.2 billion facility to detain 5,000 migrants. The administration started detaining migrants there in August, yet it remains a construction site as it grows. When completed, it will be the biggest migrant detention facility in the nation.

Camp East Montana is historic not only for its size, but also its location. The facility is nested within Fort Bliss, a military base that served as an internment camp of Japanese Americans during World War II—a policy dependent on remote federal land, where witnesses simply don't exist.

It’s now the first large-scale immigrant detention site located on a military base, insulating it from journalists, attorneys, and advocates, serving as a pilot model that the administration hopes to replicate across the country. Human rights groups warned that this design would trigger a crisis. In the half-year since Camp East Montana’s inception, they’ve been proven right.

Almost immediately after its opening, reports emerged of human rights abuses at the facility. In September, Congresswoman Veronica Escobar visited and witnessed detainees being fed rotten food and unsafe drinking water. By December, the ACLU, Human Rights Watch, and several Texas-based immigrant and civil rights groups had collected 16 sworn declarations from immigrants detained there. The declarations describe widespread abuses, including excessive force, denial of medicine and food, and sexual abuse.

Then, people started dying.

Deaths behind Doors

It started on December 3rd. Francisco Gaspar Cristóbal Andres, a 48-year-old from Guatemala, died of what ICE described as “natural liver and kidney failure.” Cristóbal Andres’ widow, who had also been detained at Camp East Montana until the days immediately before Cristóbal Andres’ death, stated in an interview with the El Paso Times that he had no health concerns before entering ICE detention.

On January 9th, ICE released another public notification, then about a detainee by the name of Geraldo Lunas Campos who had died at Fort Bliss nearly a week earlier on January 3rd. ICE’s notification went into detail about Lunas Campos’ extensive criminal record, but was vague about his cause of death, stating only that he was pronounced dead after experiencing “medical distress.”

Lunas Campos’ death, however, did not vanish from public view as quickly as Cristóbal Andres’. That’s because when the El Paso County Medical Examiner's Office completed the autopsy report, they found that his body showed “signs of struggle” and “hemorrhages on his neck.” The deputy medical examiner Dr. Adam Gonzalez determined that he died of “asphyxia due to neck and torso compression” and ruled the death a homicide. A witness confirmed the medical examiner’s determination, telling the Associated Press that Lunas Campos was, “handcuffed as at least five guards held him down and one put an arm around his neck and squeezed until he was unconscious.”

Following the medical examiner’s report, DHS spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin amended the Department’s statement, saying that he died while “violently resisting” security staff as they tried to stop him from taking his own life.

Five days later, 36-year-old Victor Manuel Diaz died while in ICE custody. Three deaths from the same facility in 44 days. In a January 18th statement, ICE claimed that Manuel Diaz was found unconscious and unresponsive by security staff, and that his death was presumed to be a suicide. However, his family told ABC News that they do not believe that he killed himself, and they are calling for a complete investigation of his death.

According to Diaz’s family’s attorney who spoke with the El Paso County Medical Examiner’s Office, when the office attempted to take custody of Diaz’s body to conduct the autopsy, DHS refused to transfer custody, instead sending Diaz’s body to the William Beaumont Army Medical Center in Fort Bliss. His body remains on military property. There may never be an independent determination of how he died.

Dilley: Screaming for a Witness

Five hundred miles southeast of Fort Bliss, children are pushing back. At the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Texas (informally known as “Dilley”), detainees have been engaged in a multiple-day protest.

Dilley, originally established by the Obama administration for the detention of migrant children, now detains over 1,000 people, many of them minors. As with Camp East Montana, detainees at Dilley have accused ICE of denying them adequate medical care and safe drinking water.

Then, Liam Ramos, the five-year-old who was detained in Minnesota while wearing his Spider-man backpack, arrived to Dilley. His detention—reportedly the result of ICE using him as bait to lure his father into ICE custody—has been as much a point of consternation inside the detention center as it has been outside of it. His arrival triggered a wave of protest by the families and children inside its walls.

As the protests erupted, the architecture of invisibility engaged. Eric Lee, an immigration attorney who was visiting his clients in the facility when the protests broke out, was ushered out of the building. From outside the walls, he recorded himself describing what occurred, with detained children in the background chanting “let us out” and “libertad.” Almost immediately, another voice can be heard, “Put away your camera! That’s not allowed! Get off of the premises now!”

Source: Eric Lee

Dilley is showing that ICE’s ability to hide conditions in detention centers can be broken. Drones, flying above the facility, captured the protesting families gathered in the facility’s courtyard, and detainees have started getting their message out.

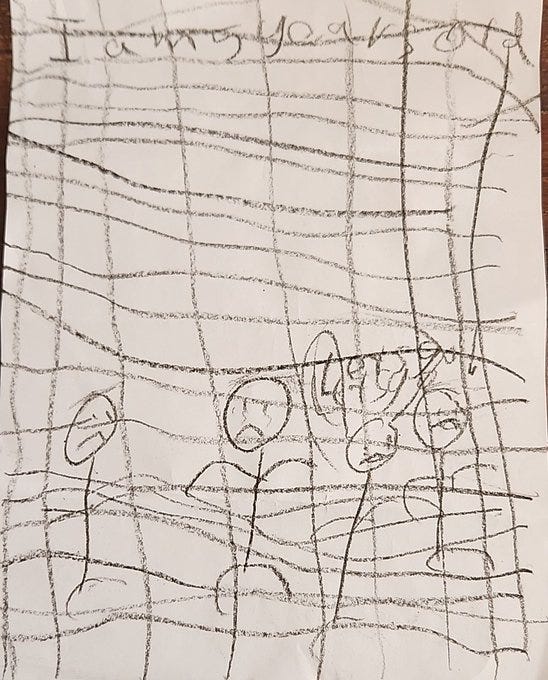

Maria Alejandra Montoya, a woman who has been detained at Dilley with her 9-year-old since October, shared with the Associated Press, “The message we want to send is for them to treat us with dignity and according to the law. We’re immigrants, with children, not criminals.” Other, younger detainees have shared their perspective through drawings given to their attorneys:

Manufactured Invisibility

Many will be celebrating the news of Greg Bovino’s demotion, a small measure of accountability made possible because Minnesotans witnessed, recorded, and refused to look away. Their cameras proved that DHS's accounts were lies.

But inside detention, DHS controls the cameras. When someone dies at Camp East Montana, there is only ICE's account—and the silence they've built around it.

Dilley shows that the wall of silence can be breached: with drones, with chanting, with sheer persistence. But Fort Bliss was designed to make that impossible. Victor Manuel Diaz's body is still there. We may never know how he died.

Excellent writing and reporting of such important and horrific accounts. Thank you for this. Keep doing what you’re doing.

You left out the part where the 5 year old's dad abandoned him when ICE showed up.

The kid is not being used as bait, the deadbeat dad just does not care enough about his child to take care of him. The dad refuses to take accountability for his violent crimes and the victims he has harmed.